Kelly Washbourne

Kent State University

Aceptado: 30 octubre 2024

Reader: Will you buy a Glass, a Mirror that flatters not? Bid fair, here 'tis that will shew you your whole proportion; for it represents the greatest part of the world Fools and Knaves; and 'tis two to one but you may see your self here.

(Anonymous, Preface to the 1657 translation of The Life and

Adventures of

Buscon the Witty Spaniard)

¿Qué son las muchas [traducciones] de la Ilíada de Chapman a Magnien sino diversas perspectivas de un hecho móvil, sino un largo sorteo experimental de omisiones y de énfasis?

(Borges, “Las versiones homéricas”, 1973)

Introduction: The Picaresque and Translations of El Buscón

Many are the ways a 'public reading' of a text can be performed, including literary criticism, marginalia, declamation, staging, and translation. The latter in particular makes visible the interpretive textures, and readers' conclusions if not always the processes, involved. A stereoscopic reading (Rose, 1997), also called, with a different conceptualization, parallel or multi-version-reading (Berlina, 2014), are side-by-side readings of translations that can bring rich points into relief and thus show us new dimensionality and variability in texts.

The text for stereoscopic treatment, El Buscón by Francisco de Quevedo, is a classic of its genre, the picaresque narrative. Friedman (2015: 5) offers many of the central features of the picaresque as narrative realism; satire and parody of the subject and of society; a hero from the lower class and having tarnished parentage, a first-person narration, the search for upward mobility; movement, development, even transformation; complex, often indecipherable language; authorial intervention; irony; unity despite the episodic nature; and a Horatian dulce et utile guiding philosophy. Guillén (2000: 41) admirably defined the picaresque as “the fictional confession of a liar”. While we will not join the debate (nor the abuses and indiscriminateness of the term's application—e.g. the discussion in Allatson 1995—particularly outside its original moment), we find the class factor apropos to translation. We are concerned here with depictions of low life, as the literature calls this world, what José Luis Alonso Hernández (1976) calls the era's léxico del marginalismo. This study will consider select passages related to ways that three phenomena in the text are bound up with one another, especially insofar as they pit speakable and unspeakable, low and polite, against each other: 1) the body and its taboos; 2) social status (particularly connected to ascendancy and religion); and 3) illegal or immoral acts. The novel's aggressive jester humor is especially a tonal challenge to the translator (see Roncero López's 2010 book on high [eutrapelic] and low [non-eutrapelic] humor; εὐτραπελία, eutrapelia, refers to a classical conception of an appropriate attitude toward humor, avoiding the extremes of boorishness and humorlessness). While critics have debated the extent to which the novel is in fact picaresque, and whether its purpose is moral-didactic, the book commands our attention for its sordidness. Though escaping condemnation by the Inquisition due to its author disavowing it, the work is filled with “the language of hypocrisy and deception, folly and violence” (Clamurro, 1980: 296; see also Weinstein, 2016: 31-50, who calls the work a dehumanizing one in which “people are no more than their bodies”, 33).(1) The violations of decorum were possible in that the common people depicted were objects of laughter, not yet pitiable; it was not until after 1800 that unseemly depictions of low life began to transform into the sentimental, and then only gradually, as the sufferings were for a long time unworthy of sympathy (Dickie, 2011: 4, 111-12). Translations done in the eighteenth century were then meeting with a new consciousness of “humility and equality before God” and this in turn was “combining with emerging benevolist [ideals] to make older forms of laughter problematic” (ibid., 125).

Let us consider the corpus of translations into English of Francisco Gómez de Quevedo's La vida del buscón (editio princeps 1626), which can be reconstructed chronologically as follows:(2)

Quevedo, Francisco de, The Life and Adventures of Buscon the Witty Spaniard, translated by John Davies, printed by J.M. for Henry Herringman, London, 1657 [published anonymously, depends on the 1633 French].

— Pleasant Story of Paul of Segovia, translated by W. B., in: Gonzalo de Céspedes y Meneses, The famous history of Auristella originally written by Don Gonsalo de Cepedes; together with the pleasant story of Paul of Segovia, printed for Joseph Hindmarsh, London, 1683 [abridged].

— The Pleasant History of the Life and Actions of Paul, the Spanish Sharper; the Pattern of Rogues and Mirror of Vagabonds in Comical Works of Don Francisco de Quevedo, translated by John Stevens, London, John Morphew, 1701/1742.

— The Life of Paul, the Spanish Sharper in The Works of Quevedo, translated by Pedro Piñeda, London, E. Commyns, 1745.

— Pablo of Segovia the Spanish Sharper, London, Unwin Brothers, 1892 [Pedro Piñeda's revision of John Stevens's Quevedo’s Works, Edinburgh, 1798, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/46125/461 25-h/46125-h.htm].

— The Life of the Great Rascal, in: Charles Duff (rev. and ed.), Quevedo: Choice Humorous and Satirical Works, London-New York, George Routledge & Sons Ltd.-E.P. Dutton & Co., 1923.

— The Life and Adventures of Don Pablos the Sharper, translated by Francisco Villamiquel y Hardin [pseud. of Frank Mugglestone], Leicester, The Minerva Co., 1928.

— The Scavenger, translated by Hugh A. Harter, New York, Las Americas, 1962.

— Lazarillo de Tormes and the Swindler: Two Spanish Picaresque Novels, translated by Michael Alpert, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1969 [second edition consulted herewith, 2003].

— Lazarillo de Tormes and The Grifter (El Buscon): Two Novels of the Low Life in Golden Age Spain, translated by David Frye, Indianapolis-Cambridge, Hackett Publishing Company, 2015.

Beatrice Garzelli (2018: 212) voices what surely are universal problems in translating the novel: the sheer proliferation of witticisms, symbols, wordplay, ambiguities and ambivalences, references to unstable sources, irony and sarcasm, and 'distortions' and 'deformations' of idiomatic speech. The risk, she notes, lies in not “mitigar demasiado las imágenes subversivas y transgresoras, al contrario, exagerarlas hiperbólicamente o, también, explicarlas de una forma que Quevedo rechazaría” (ibid.). Overexplaining jokes can easily incur overtranslation, perhaps in a way that paratextual commentary often does not, inasmuch as a joke is performed to create sudden insights or relationships, not belated, intellectual ones. This doubling or tension appears throughout, not only in jokes, and especially in the visual or material reality that must be translated along with attendant cultural practices. For instance, in chapter one, the narrator tells us, “Muchas veces me hubieran llevado en el asno si hubiera cantado en el potro”, animal imagery that works through doubled discourse as cultural signifiers: the donkey (asno) was used to parade prisoners through the streets on the way to jail; the colt (potro) is the rack, a torture device. A fundamental shift preoccupies the translator of the novel: that “language continually moves away from the norms of representational fiction and toward a more self-referential use of words”, creating a schism between language and reality, “not only in the duplicities of the pícaros and other tricksters but also in the alienation and self-deceptions of those who are captives of their own languages” (Clamurro, 1980: 298).

The issue of who translates is as relevant for our purposes as how one translates. “The Buscon,” we are told, “shorn of much of his stature, was Englished by a person of quality [John Davies's anonymous translation] so early as 1657, with a dedication to a lady. It was still further reduced in 1683, both in size and art, though most of the grossness was left untouched” (Watts, n. p.). Antecedents of sociological interest in the translator biography are found in such endorsements; in essence, the assumption is that a right-minded translator would not only know what techniques to use, but would also be of sufficient character to be trusted to translate the work. One can find many translations from the mid-seventeenth-century that used this conventional phrasing “person of honour”, a dubious marketing claim, according to Line Cottegnies, that projects an aura of socially aspirant gentility (2019: 320). In the case of picaresque literature, it is easy to see how it might redeem the 'low life' subject matter in the minds of the new middle class, who wanted titillation without the stigma of prurience. Further evidence of this claim may be found in a single detail: From 1683 to at least 1742, titles in the English editions called the text the pleasant story/history, which its grotesqueries and mordant serio-comic critiques, and anti-models of behavior, prevent it from being wholly. The translators must walk a fine line in the rhetoric of establishing their ethos, or trustworthiness, and of assuaging what Belle (2018: 64) calls translators’ “status anxiety” in early modern literature, in which proxies such as editors partook.

Concern for respectability naturally extends, too, to the novel's dialogue. Class consciousness is manifested in concerns over the perceived violation of taste that verisimilar translation of diction would present, as life and literature were held to separate standards; Pedro Piñeda's strong command of Spanish

recommended [him] to the editors of the edition of Quevedo's Works, published at Edinburgh in 1798, as a person fit to revise and correct the version of Mr. Stevens. That version, though not satisfactory in all respects, is still the best we have in English. It is almost too faithful to the original in respect that it retains many expressions, phrases, and words, of the kind in which Quevedo loved to indulge, which, however appropriate in the mouths of the speakers in a thieves' den or a convict prison, are scarcely delicate enough for the taste of the modern English public, or necessary to bring out the full humour of the story. (Introduction by Henry Edward Watts to the 1892 translation, my emphasis.)

Watts’ words flatter the sensibilities of the ‘gentle readers’ to disarm their defenses: by claiming the works are in some sense beneath the readers, they are free to indulge in reading them without guilt by association. Linguistic indulgence on Quevedo's part produced many kinds of response, as we will see, but the plot itself was manipulated translationally by Sieur de la Geneste (the pseudonym of Paul Scarron) in L'Aventurier Buscon (1633) (Bjornson 1977: 135). La Geneste made over the novel into an adventure story, featuring even more scabrous sexuality, and a noble, sentimental hero rather than an anti-hero. Richard Bjornson notes that the “panorama of representative vices and follies remains an integral part of the novel, but satirical condemnation of the pícaro's vulgarity and presumptuousness completely disappears” (ibid., 135). In fact, L'aventurier Buscón completely changes the open ending of the work to Pablos falling in love with a merchant's daughter and staying on to serve in her house. This undercuts the satire around a character who cannot rise in his station. Although the novel's last line sounds a moralizing, pessimistic note —"Y fuéme peor, pues nunca mejora su estado quien muda solamente de lugar, y no de vida y costumbres”— the happy ending in the 1657 English translation follows the French’s whole cloth invention:

she left me in Rozeles right, the Inheritance, and Goods of her house, which amounted unto one hundred thousand Crowns. Having thus fixed and setled my fortune by Alistors help and conduct, it was but reasonable to make him some acknowledgment and reward, for the services he had done me [...].

Thus Gentle Reader you have seen the issue of my adventures; but for as much as no one can be called happy before his death, I know not whether amidst so many good fortunes, some disaster may not intervean [...].

Every thing is in the hand of Providence, we cannot foresee what shall be after us; yet for the present I think I may safely say, there are few men in the world, who for happiness may compare with my self. (287)

Such interpolations can cause a work’s entire moral force to shift.

Pablos's Father

Let us consider some textual passages. One of the well-known jokes about Pablos's parentage comes at the father's expense:

Dicen que era de muy buena cepa, y, según él bebía, es cosa para creer. (Chapter 1, 66) (3)

Cepa is polysemous: stock, but also vine, thus metonymically wine. Thus a translator could proceed associationally: 'fine stock' >> 'fine grapevine stock', or vine >> fruit of the vine, or another direction altogether. I propose “he was a man of good stock: when the good stock of wine came in, so did he.” [This pun hints at, but ultimately denies, the father's nobility, and affirms his drunkenness.] Some published translations follow (emphasis mine in all examples; all examples Quevedo):

[Omitted by translator.] (1657)

They say he came of a good stock, and his actions showed it. (1892, also 1742: 100) [Deviant sense, missed pun.]

It was said that he came of good stock, and, to judge by his love for the pot, this can easily be believed. (1923: 3)

He was said to come of good stock, which may well be so—he could drink with the best. (1928: 11)

People said he was of very good stock, and to judge from the amount that he drank it's believable enough. (1962: 23) [This translation somehow equates high class with heavy drinking.]

They say he came from very good stock, and that's not hard to believe considering how much liquid he consumed! (1969/2003: 65) [This pun turns on 'stock' in the sense of the basis of soup or sauce; a fine enough pun but the intimation of drunkenness is faint.]

In book 1, chapter 2, the father is called a 'gato' by someone at school: “otro decía que a mi padre le habían llevado a su casa para que la limpiase de ratones, por llamarle gato” (71). The translations read:

that my Father had been sent for to his house to drive away the Rats, as much as to say, he was a Cat. (1657: 9-10)

that my father had been sent for to his house to frighten away the vermin, for nothing was safe where he came. (1892 and 1747: 103)

another said my father had been called in to his house to clear it of mice, as he was nothing but a tom-cat.(1) (1) Gato: rat and thief. (1928: 17) [The translator confesses on page eight that puns would have to be rendered with footnotes.]

that my father had been brought to his house to clear out the rats, which was a way of calling him a house-breaking old tomcat. (1962: 26) ['Tomcat' skews sexual as slang, though 'house-breaking' tempers that sense.]

Another called my father a cat-thief and said his family had employed him to kill mice. (1969/2003: 68)

which was a way of calling him a cat burglar. (2015: 63)

William Gibson (2007: 585 n. 54) glosses the 1742 version:

An eighteenth-century translation that preserves the spirit of the pun reads, “I suppose the Pastry Cooks here-abouts will soon ease us of that sad Spectacle [the corpse lying in the road, feeding the rooks], burying him in their minced Pies.” In Spanish the pun is that the father’s corpse was quartered (cuarto), while the meat pies cost four (cuatro) maravedís, or pennies. (La vida del Buscón, 143, and [...] (1742), 136)

[Source text: Hícele cuartos, y dile por sepultura los caminos; Dios sabe que a mí me pesa de verle en ellos, haciendo mesa franca a los grajos; pero yo entiendo que los pasteleros desta tierra nos consolarán, acomodándole en los de a cuatro. (Chapter 7, 111)]

The father is further dehumanized through such black humor.

Pablos's Mother and Sexuality

John F. Knowlton describes the translator's dilemma of multiple overlapping semantic fields in his analysis of a particularly overdetermined image:

“Padeció grandes trabajos recién casada, y aun después, porque malas lenguas daban en decir que mi padre metía el dos de bastos por sacar el as de oros” is translated by Hugh Harter as follows: 'Her tribulations began when she was first married and continued long after as sharp tongues declared that my father had very nimble fingers for other people's gold.' The suggestion that Pablos's mother was a prostitute, as well as his father's attitude toward her activities, disappear in the translation. Perhaps something like “he didn't mind wearing horns—'dos de bastos'—if he were paid for it.” (1967: 125)

In fact, the image has been read as sexually charged as well (see Rodríguez and Ledoux 1994, for example), in addition to invoking playing cards, most obviously, and the 'tomadores del dos' (rateros) of street slang. More examples from the corpus follow:

some of our Neighbours tongues were so lavish as to report, that she had changed the Roman I of my Fathers name into a Greek Y (1657: 2)

my father was willing to wear the horns, provided they were tipped with gold (1892: 4; also Stevens 1742: 100, [tipp'd])

evil tongues said that my father found things before they were lost (1928: 12)

my father had very nimble fingers for other people's gold. (1962: 23)

my father picked his customers' pockets (1969/2003: 65)

my father would use the two of clubs to take the ace of diamonds.* (* That is, he was a pickpocket, using two fingers to pinch a man's purse. Also the two of clubs is the lowest-ranking card in the Spanish card deck, while the ace of gold coins [equivalent to the ace of diamonds] is the highest; only by cheating can you take an ace with a two.) (2015: 60, 60 n. 4)

But the card imagery is compensated for a page later to fully render the segment “alcahueta y flux para los dineros de todos”:

Unos la llamaban zurcidora de gustos; otros, algebrista de voluntades desconcertadas, y por mal nombre alcahueta y flux para los dineros de todos.

Some called her the Bone-setter of dislocated affections, and othersome of the more vulgar sort, stiled her in plain English, Bawd, and said that she played at all Games for money (1657: 3)

Some gave her the Name of a Pleaƒure-Broker, others of a Reconciler; but the ruder ƒort, in coarƒe Language, call'd her down-right Bawd, and univerƒal Money-Catcher. (1742: 100)

for an ill name, she was dubbed a bawdy procuress and a bottomless pit for all men's money. (1923: 4)

To some she was the card in the three-card suit, but she was an ace in the hole to all the men and a straight flush after everyone's chips. (1962: 24)

The 2015 translation is chock-full of information both encoded in the text and paratextually in the translator's note; it strengthens the thievery implied by the image, although all translators underplay the aggression of the use of bastos in securing oros. David Frye in his introduction confides, in what amounts to a translation ethics of representation: “How to translate the slurs that [Quevedo] puts in his characters' mouths? It would be dishonest to censor or silence the ugliness; I have translated each slur just as it occurs, distasteful as I find them. Let the reader be warned. This is part of our literary legacy, and we should know it and recognize it, the good with the bad” (2015: xxxiii). Frye's notes, in the thick translation or textual scholarship tradition, unite the semantic field of thievery in pointing out what translators failed to account for: barber, shearer, and tailor (barbero, tundidor, sastre) all were words for thief in Quevedo's time (2015: xxxiii, 59 n. 2).

When Pablo learns of his uncertain parentage, he narrates:

Roguéle que me declarase si pudiera haberle desmentido con verdad, o que me dijese si me había concebido a escote entre muchos, o si era hijo de mi padre. (72)

The phrase serves to characterize a shamed Pablos but through his inchoate understanding of sex. In translation, this communal fatherhood, “splitting the bill”, as it were, is called everything from “begot in a Huddle, by a great many” (1742: 103), to “begot in a quota system for many or was the son of my father alone” (1962: 27), to “whether I was really the son of my father and not the son of a stud” (1928: 18). Pablos is called (perhaps with searing irony), “extraordinarily begotten” in the 1657 translation, a phrase with accidentally supernatural overtones. The 1923 text uses an omission strategy to ignore the sexual lottery altogether: “Was I really and truly the son of my own father?” (7). The two most contemporary versions take new directions: “accidentally by any number of men” (1969/2003: 69), and “whether I had been conceived buffet-style by many men” (2015: 63). But it is Frye (2015) who renders a phrase related to the mother's promiscuity that translators neutralized for four centuries, while also distancing himself from the indecorous image:

Source text: todos los copleros de España hacían cosas sobre ella. (67)

Every published translation but Frye's restricts the sense here to poetasters rendering poetic compositions in the mother's honor (e.g. “made Verƒes of her”; 1742: 100). Garzelli spotted this possibility as well (2018: 217), as did Angel Basanta, the editor of the Castalia edition (Quevedo, 1986, 67), but mostly translators leave the joke untouched. Frye embraces the insinuation, however, while distancing himself:

every songster in Spain did things on her* (* The crude double entendre is Quevedo's.) (Frye, 2015: 59, 59 n. 3)

One might not be far wrong in suspecting that Quevedo even had something in mind with making coplero confusable for copulero ('panderer').

Translators' handling of humor or wit, then, often hinges on whether or not they supply the unspoken in an utterance. In chapter 3, to offer another example, consider Cabra's nose: “se le había comido de unas búas de resfriado, que aun no fueron de vicio, porque cuestan dinero” (78); the 'vicio' is sanitized in 1969/2003:

poxy with cold sores (not the real pox of course; it costs money to catch that) (1969/2003: 73)

The 1928 translation hints at more:

rheum (it could not have been vice, for indulgence costs money) (25)

But the 1962 translation (32) makes sure the most innocent of readers does not fail to miss the implication:

worn flat by sores, from colds, but which one would have thought to come from the French disease except that that illness involves the price of a girl. (32)

The explict mechanics of venereal disease combine incongruously with the centuries-old euphemism, 'French disease'.

One scene obliquely invokes what 'dare not speak its name', and most translators risk outright obscurity here. In book 2, chapter 4, in prison, Pablos meets 'el Jayán', which we find out, after vaguely named crimes, is doing time for criminalized homosexual acts; the Spanish and translations follow:

Llamábanle el Jayán; decía que estaba preso por cosas de aire, y así, sospeché yo era por algunos fuelles, chirimías o abanicos. y a los que le preguntaban si era por algo de' esto, respondía que no, sino por pecados de atrás, y pensé que por cosas viejas quería decir, y al fin averigué que por puto. (170)

He was called the Giant, he told us, he was in for a trivial windy matter, which he valued not, I supposed then, that he was in for some Bellowes, Bag-pipes, Foot-balls Fans, or the like; but when we asked him if it were for any thing of that nature, he told us, not, but for some post-dated sins. I thought then he had been a Long-lane Merchant, and had sold old for new clothes, but at length after much enquiry, I discover'd he had been in love with the masculine Gender. (1657: 211)

they call'd him the Gyant, and he ƒaid of himƒelf, that he was in Priƒon for petty Trifles, which I concluded to be ƒome meer Larceny, and if any Body aƒk'd him whether that was the Crime, he anƒwered in the Negative, but that it was for backward Sins; I fancied he had meant ƒome old Offences, according to their Cant, but at length was informed he was there for Sodomy. (1742: 186) [“according to their Cant” is a metalinguistic interpolation that offers a pretext for the euphemism, and locates the narrator as an outsider to thieves' slang]

He was nicknamed the Giant. He said he had been arrested for windy trifles, and so I surmised he was referring to bellows, shawms, or fans. To those who asked him if it was any of these, he replied that it wasn't, but rather for posterior sins. So I thought he meant old things past and gone, but at last he confessed he was a pædicator. (1928: 154)

He was called Big Burly. He told that he had been locked up for airing things, so I suspected it was on account of bellows, a flute or a fan. To anyone who asked him if it was because of these things he answered that it wasn't, that it was for things he'd put behind. I supposed he meant for things far in the past. Finally I found out that he was in for sodomy. (1962: 107)

They called him the Giant, and he was in prison for something to do with wind, so I thought he had stolen some bellows or musical instrument or even fans. When people asked him if it was anything like that he said no; it was for posterior crimes. I thought he meant old crimes, but at least I realized it was because he was a queer. (1969/2003: 154-55)

They called him the Giant. He said he had been arrested for flighty things, and I supposed he meant that some stool pigeon had let fly with a denunciation of him, but when I asked if it was anything of the sort she said no, it was just about sins that were behind him. I thought he meant things from his past, but at least I discovered it was for sodomy. (2015: 141)

A few observations are in order: puto can also be prostitute (hence: gigolo), calling attention to whether the Jayán is in jail for his sexual orientation, or for specific acts (note that no translator uses 'sodomite'). The circumlocution of the 1657 translation throws the issue into high relief. Second, in germanía the fuelles, chirimías o abanicos are all metonyms for soplones (Quevedo 1986: 121n21), thus activating the sense of 'informant', which Frye tries for gamely by connecting 'flighty things' to 'stool pigeon'.

Religion

Religion plays an inescapable role in the text, and translation has both accented and effaced it over the centuries. Garzelli (2018) has taken note of the passage evincing of the mother's ambiguous status as a conversa, an inescapable theme tied to blood purity in 17th-century Spain (see also Parello 2011). Translators into English manipulate the degree of ellipticality with which the tension between cristianos viejos and cristianos nuevos is conveyed in the text:

She was of the race of the Jews (1657: 1)

the town fully ƒuƒpected that ƒhe was of a Jewiƒh Race (1742: 100)

The town fuly suspected she was no old Christian (1892; plus footnote: “i.e. she was a Jew”)

the town suspected that she was not of pure old Christian* blood (1923: 3; plus footnote)

There was a suspicion in town that she was not an old Christian (1928: 11)

People in the community suspected that Mother was not of pure Christian blood (1962: 23)

The townspeople suspected that she had some Moorish or Jewish blood in her (1969/2003: 65)

the townspeople suspected she was not an Old Christian (even when they saw her grey hair and ragged clothes) (2015: 59)

Henry Ettinghausen comments on the racial overtones of the father's churchgoing as not “de puro buen cristiano”, just as some translators supply more interpretive cues in the passage above. He makes much of Pablos's use of “Estudié la jacarandina y a pocos días era rabí de los otros rufianes” (III, 10) (1987: 216). In addition to rufián itself having a sense of 'pimp' (at least as far back as de Nebrija [1495?] 2005), deactivated wisely here in all versions, translators have missed the significance in the boy's rejection of the converso heritage, only to become the 'rabbi' of the gang in the end. Partly a metaphor for the wisdom of Jewish scholars, and partly for his leadership, the word is neutralized by a secularized translation, as many employed:

I made a study of thieves' Latin and soon became chief priest of the thieving crew. (1928: 220) [The phrasing accords with the semantic field of Pablos as an “obstinate sinner” in church in the final scene]

I studied up on thieves' ballads and soon was cantor to my whole troupe of thugs. (1962: 146)

I took a good look at Seville low life and in a few days I was the gang leader. (1969/2003: 196)

The narration prepares us for this ennobling language right from the prologue, where the lessons are described as 'sermones', ambiguous warnings to the good reader while also appealing to their low impulses. Here is the 1928 version:

To the Reader: And even though you should ignore the warnings, take note at least of the sermons, though I doubt whether anyone will buy a book of rogue's tricks to turn him away from the promptings of his natural depravity. (n. p.)

The ironic use of religious language runs throughout the text, such as “Yo le tiré dos berengenas a su madre cuando fué obispa” (72)(bishop; also, headwear for witches in the Inquisition) in book 1, chapter 2, or the 'cardenales' (ambiguously, meaning both the senior clergy members and welts from flogging) that rain down on Pablos's father. Even dead metaphors are shot through with religious overtones; e.g. in chapter 10, book 3, the game of cards is described as being “concebido en pecado” (211), or the product of bastardy.

Scatology

The Carnaval scene in the market among the vegetable sellers curiously elicits dysphemistic translation—less euphemistic than the source—in the late twentieth century and early twenty-first, but not before then:

tal golpe me le dieron al caballo en la cara, que yendo a empinarse, cayó conmigo — hablando con perdón— en una privada; púsome cual v. m. puede imaginar. Y a mis muchachos se habían armado de piedras, y daban tras las verdureras, y descalabraron dos. Yo, a todo esto, después que caí en la privada, era la persona más necesaria de la riña. (1, Ch. 2, 75-76)

he began to stand on end, and being none of the strongest fell backwards together with my worship, not upon dry land, but with reverence be it spoken, into a bottomless Jakes, which to my misfortune was there at hand. I give you leave to guess with your self; how sweetly I was pickled. (1657: 16-17)

my Horfe received fuch a Shot in the Head, that as he went to rear, his Strength failing him, we both came down into the Kennel. You may imagine what a Condition I was in. (1742: 105)

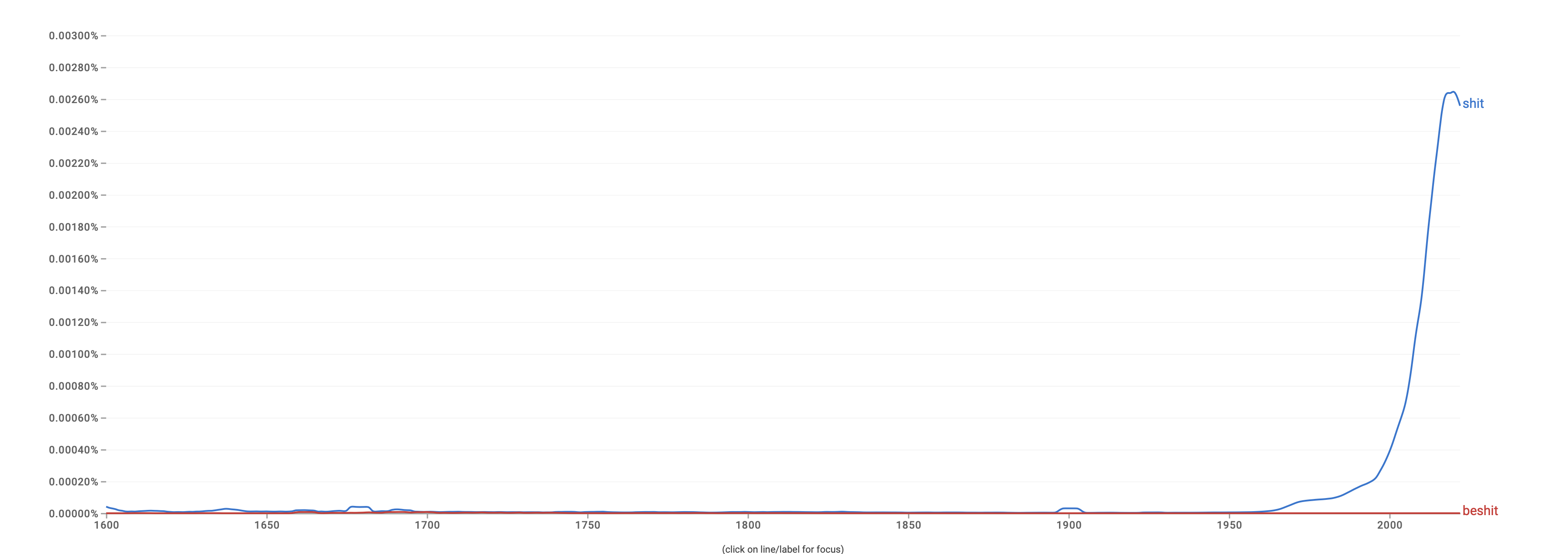

And the ensuing scene, when Pablos is interrogated by police: “... whereunto I answered all beshit as I was; that I had none offensive as to matter of life, but only to the sense of smelling." (1657: 17) [“al cual respondí, todo sucio, que si no eran ofensivas contra las narices, que yo no tenía otras”, p. 76]. Here the double meaning of 'offensive' is straightforward, and most translators handle it easily. For its part, 'beshit' (and 'shit') had two zeniths in print: the 1550s and the 1650s-60s, and not again until the late 20th century:

Fig. 1: Google Ngram occurrences of “shit" and “beshit”, 1600-present

Oxford English Dictionary notes 'beshit' is 'Obsolete in polite usage', suggesting it once was polite.

To continue with the market scene:

he reared and fell with me—begging your pardon!—into a necessary. You can imagine what sort of state I was in!" . . . As for me, my fall into the privy had made me the most necessary person in the fight. (1928: 21) [The repetition spoils the mechanics of the joke, as 'necesario' is a euphemism for 'latrine'; however, 'necessary house', peaking in currency in 1785, is a valid lexeme for an outhouse.]

both fell—pardon my frank speech—into an open privy. [...] after my fall into the outhouse, I was the most diSTINCtive person in the fray. (1962: 30)

it reared up and fell down and brought me down with it into the pile of (excuse me) shit. You can imagine the state I was in. . . . After I had fallen into the muck I turned into—literally—the shittiest fighter of the lot. (1969/2003: 71) [The translator dysphemizes 'necesario' and adds a pun on 'shitty' meaning 'poor'.]

it reared back and we both fell into—begging your pardon—an open latrine. You can imagine what that did for me. . . . Meanwhile, my tumble into the latrine had left me alone privy to the battle's progress. (2015: 65)

Another comic scene (Book I, chapter 3) is described across a spectrum of euphemism, and involves 'gaitas', a word now in disuse for enemas. In translation these are called, among other things, 'a Potion backwards' [1747]); the comedy arises in the dehumanizing scene invoking a turkey basting gone awry.

The initiation scene at Alcalá (chapter 5) features spitting: “ya estaban juntos hasta ciento. Comenzaron a escarbar y tocar al arma; y en las toses y abrir y cerrar de las bocas vi que se me aparejaban gargajos" (95). In the 1892 translation the footnote reads: “* n. 10: “There is a scene here which will not bear an English dress. The scholars stand around and spit at Pablo. There is no other humour of which the reader is deprived.” Victorian sensibilities accommodate the plot's stabbings, thefts, swindles, etc., but not spitting. Only the 1747 edition goes so far as to transform the spitting into something explicitly pathological, a contagious horse disease, gla(u)nders (muermo).

Title and Protagonist: the buscón, the pícaro, and related scoundrels

Alfonso Rey argues that the satire and moralizing are effaced in the European translations of the novel's title, creating a book “that is essentially ingenious and fun” (2010: 129). The title, Historia de la vida del Buscón, llamado don Pablo, ejemplo de vagamundos y espejo de tacaños, has been approached with multifarious strategies. Some of the editions in Spanish include La vida del Buscavida, por otro nombre don Pablos, Historia del Buscón llamado don Pablo, Vida del Buscón, llamado don Pablos and La vida del Gran Tacaño, or simply El Tacaño, a term, now archaic, for the rogue. In French translation the romantic aventurier (wanderer, adventurer, explorer) is stressed—L'aventurier Buscón—with mere mischievousness conveyed in its subtitle (histoire facecieuse), while the Italian title sounds less like a warning to polite society than a celebration of roguery: Historia della vita del astutissimo e sagacissimo Buscone chiamato don Paulo; the German invents in Pablos the 'arch-rogue': Geschichte und Leben des Erzschelms, genannt Don Paul.

Three omissions are worth remarking in the English titles: first, the 'ejemplo' in the Spanish subtitle points to a literary form that all but disappears in most versions—that of the exemplum, the moral and didactic tale; and second, the honorific 'don' in the Spanish title is unaccounted for in every English title with the exception of the 1928 text, in which he is 'Don Pablo'. Feigned ancestry, which Ettinghausen links to converso practices (1987: 244), are signaled in such class markers. Third, the 'Vida de' formula may point to a parody of hagiography (Rey, 2010: 127). Indeed, many other interdiscursive and intertextual nods can be found, such as parody of advice literature for rulers, compositions known as specula principum, 'mirrors for princes'. As for additions, the tendency to nationalize the protagonist—e.g. 'witty Spaniard'—is marked, then abandoned in contemporary translations (after 1892).

Pícaro, for its part, goes rogue in translation. The Diccionario de Autoridades defines a pícaro as “el que hurta rateramente, o usa con malicia y arte de sacaliñas para estafar” (1726-1739, ctd. in Garzelli 2018: 213). Garrett (2015: 99) reminds us of its relation to picar, thus the pícaro 'pricks' or punctures the pretensions of social betters. A term can become historically bound—rogue, rascal, scoundrel, picaroon—through semantic drift. Frye notes: “these honor- and shame-based epithets [pícaro and bellaco] are as out of fashion today as the concept of aristocratic honor itself” (2015: xxxii). The hero has been named a sharper (described in Bailey's (1721) canting dictionary as “a Cheat, one that lives by his Wits”), a scavenger, a rogue, a rascal, a swindler, a grifter, and even a 'Buscon', a coinage in English. 'Swindler', first attested 1686, and 'grifter' (1865) have endured in common currency, but 'sharper' (1681) and 'rogue' (1489) have not, although the latter has come to describe things that are wayward or tricksters. The word 'vagabond' has undergone a change in semantic prosody: once a tougher character, related to a nomadic, unoccupied life of loafing and disreputable activity, in time it came to connote romantic wandering more exclusively. A 'buscavida' similarly now signals ambition and minding others' business, and perhaps has lost the sense of errancy in life. Where critics have been helpful here is in mapping the pícaro at the edge of criminality, and certainly as not being associated with killing (e.g. “The picaresque novel is the produce of some sort of instability, mobility or uncertainty in the social structure that permits or commands the emergence of the pícaro, an individualist and a rogue but by no means a criminal” [Katona, 1969: 87]). This matters for the translator because a pícaro then never totally loses sympathetic connection to the audience (consider the vast difference between 'scavenger' in this sense, and what today we might call a 'hustler'). The distinctions between categories of pícaro matter as well:

By the end of El Buscón, Pablos [...] uses the sword for its intended purpose while explicitly distancing himself from pícaros, not in a return to the innocence of his youth, but in the capacity of a bravo or killer. In the final scene of the novel [chapter 10], as a night of eating, drinking and subsequent catchpole-killing begins, Pablo mentions a detail that gets lost in translation. In English, the detail is “Supper time came and we were waited on by four great toughs of the type that are called strong-arm men” (195) The word for “toughs” in the original is pícaros. Additionally, the translation completely ignores that the cited 'strong-arm men' are called so by bravos, who themselves are toughs, if not killers. That toughs or killers call others 'toughs' is strange, and it only makes sense if we look at the original Spanish word from which 'strong-arm men' was translated, namely cañón. [T]he criminal slang word cañón means either a snitch or, in Galicia, a lost pícaro who has no job and no home. The translator's confusion could be attributed to the variability of a pícaro's violent nature, and does raise the question of whether a pícaro or rogue can retain this status after stabbing somebody to death. (Fernández and Snow 2017: 298)

The 1742 translation (225) distinguishes the kinds of 'toughs':

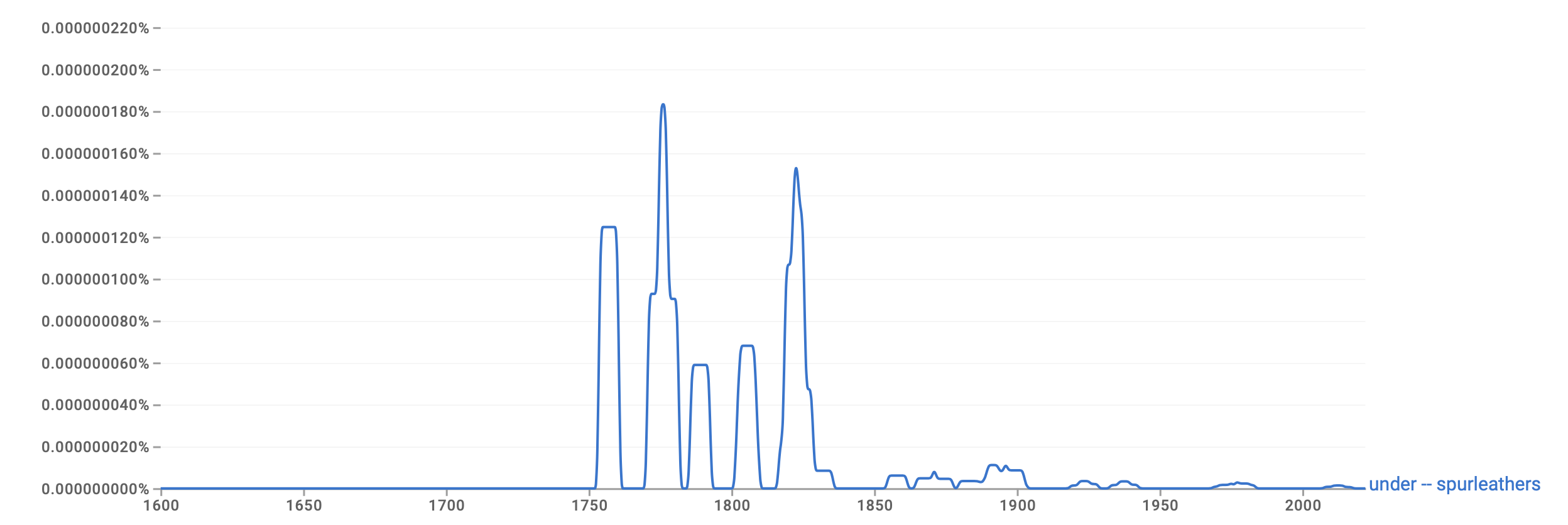

When it was Supper-time, in came a Parcel of ƒtrapping scoundrels to wait at Table, whom the topping Bullies call Under-Spurleathers.

'Under-spur-leathers' is actual cant, that is, argot, largely contemporary to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the era corresponding to the two translations in question:

Fig. 2: Google Ngram of 'under spur-leathers”, 1600-present

When time for supper came, in marched a gang of lusty scoundrels —whom the bullies call chuckers-out*— to wait at table. (1923: 135) * chuckers-out: cañones, the cant word for a rogue who is hiding from the authorities and earns his bread by waiting upon his colleagues on the 'active list'. In the case of a raid, reliance was placed upon the cañones to meet official attackers. (1923: 402 n. 135).

Supper-time arrived, and two great hulking rascals, whom the bravos call 'cannon's (1), came in to wait at table. (1) 'Cañones, a general class of thieves with no settled domicile. (1928: 218)

The 1962 text uses non-translation, a borrowing with no explicitation, to achieve a less effective distinction:

Time came to have dinner. A couple of big devils which toughs call cañones came over to the table to wait on us. (145)

The 2015 text makes a distinction:

Soon it was time for supper. Some of the scoundrels that the tough guys call 'touts' came to serve us. (2015: 178)

The tensions of self-betterment, rising above one's station, take ironic expression in other kinds of naming in the work: at the end of chapter 3 in book 2, Pablos calls his band the oxymoronic “caballeros de rapiña” (167, 'lords of larceny'), a farcical phrasing not always pursued in English: an “Order” (1657: 205); “a gang of gentlemen of prey” (1923: 90); “men of prey" (1928: 150); and “gentlemen thieves” (1969/2003: 152).

The question of how to navigate thieves' cant has elicited creative and diverse solutions. Resources for the translator, guidebooks and dictionaries of swindlers' cryptolect, include texts published as early as John Awdeley's The Fraternity of Vagabonds (1561) or Thomas Harman's A Caveat or Warning for Common Cursitors, Vulgarly Called Vagabonds (1566; in Kinney 1990). Neither was it beneath consideration for literary treatment—Charles Dickens even provided a glossary of it in Oliver Twist (1837-39). Translators take the broadest of approaches to chapter 10, book 2, from outright omission, to pleading their case for the untranslatability of the argot, to confessing their low confidence in their handling of this register:

1742 translation: no metalinguistic passage.

I will not let you farther into this secret; this is enough to make you always stand upon your guard, for you may be assured I do not tell the hundredth part of the cheats. (1892) [Null translation; no discussion of language follows the passes on marked cards; the translation avoids the metalinguistic discussion where the pícaros educate Pablos on pronunciation, merely noting “talk big, using the rough words of us gentry”.]

whereupon he gave me a sample of his Thugs' jargon.* (1923: 134): * Nearly the whole of this chapter is of a nature which renders any sort of translation liable to be called a travesty of the original. Stevens and Pineda after him, did their best, but were forced to omit whole sentences. Quevedo, like Cervantes, was a master of thieves' jargon and gipsy dialect. Here he gives full play to his vocabulary of the former; and the meaning of many words can no longer be stated with certainty. Passages omitted by Stevens and Pineda are now given; but without too much confidence in the accuracy of the rendering. (1923: 401-2 133 n)

I do not wish to throw more light on these things for you; the above will suffice to show you that you have to live with great caution, and there are an infinite number of tricks which I haven't mentioned. Dar muerte (to kill) means to win money by cheating at play; revesa (reverse) is a trick or deception practiced on a trusting friend; dobles (doubles) are those who make friends with the simple and introduce them to sharpers; blanco (white) is applied to the man who leaves his obligations blank. (1928: 215-6)

To make a kill means to win money plus property; intricacy is what the trick against a friend is called, and the reason is that it is so intricate not even the friend catches on; two-faced is the name for men who carry around coins just waiting for some purse-butcher to try to fleece them; white is what the person who is free from guile and as good as fresh bread is called; and black is the name for the player who vents his zeal on the white of the bull's eye. (1962: 144)

When they take your money, they call it 'making a killing' and rightly so; 'twist' means cheating your partner, and the game is so twisted nobody can follow what's going on. 'Suckers' mean simple people brought in to be fleeced by these swindlers. 'White' means someone who is innocent and simple and 'black' is someone who is just pretending not to know anything'. (1969/2003: 194)

Frye (2015: 176) uses “making a killing”, “double cross”; ropers”; “mark”; and “shark.” But it is in the germanía lessons from the toughs where he differs from the other translators in choosing cultural substitutions of non-standard speech varieties of a similar sociolectical standing (Cockney for Andalusian):

Repeat after me: 'aymarket, 'ogback, 'ungry, 'urt, hangry, hace in the 'ole, and jug 'o hale. (Ibid., 177)

Only in the section on marking cards in the card-sharping scene in Seville does Frye hedge his bets, noting for garrotes de morro y balestilla that these are “presumably ways of marking cards; the exact meaning is lost” (2015, 175 n116).

A profitable future direction of research in this connection would be the cross-linguistic onomastics of the novel, in the vein of Herman Iventosch's intralingual investigations, names that the critic calls “conventional allusions to rapacity and knavery”: Romo (flat-nose, from a brawl), Polanco (named for levering the spoils), Tomás de Baranda (deriving from the caló word barandar, meaning azotar), and so on (1961: 25-7).

Conclusion

Diachronic translations are works of archeology, historical-philological detective work. The strategies translators take range from modernization to nativization, from omission or censorship to euphemization, or even outright anachronism. (4) This reading exercise should remind us of the many layers to this conceptista text, the hermeneutic contributions to the work's complexity that translators provide, the images made of the text abroad, and of the different priorities, taboos, senses of humor, and norms of each age. Translators' readings, in sum, are gatekeepings, simultaneously value-laden and historically constrained. The stereoptics of multiple translations provide a dimensionality through rereadings, and demonstrate that translation inescapably is about relevance, in particular the pragmatic problem of what and how much information to provide and how prominently it is foregrounded. Importantly, translation can manipulate our sympathies: Is the novel an “indictment of antisocial behavior" (Friedman, 2015: 109) or a how-to manual of it? (5) Translations are snapshots of the state of a language at a given time, including its prejudicial, class-bound language. At the same time translation choices show the limits of what is utterable in a given age and by whom, and the changing mores that transform a text: What one age translates out, another translates back in; what one translator leaves to the reader to parse, another takes pains to spell out. Texts are never static entities, but dynamic transnational cross-fertilizations, or perhaps texts interpreted “a escote” like Pablos's own genesis, and like him, too, nomadic, elusive and not easily 'mastered'.

WORKS CITED

ALLATSON, Paul, “Policing the Picaresque: Lazarillo de Tormes and El Buscón on Trial”, Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research, 1:1-2 (1995): 119-127.

ALONSO HERNÁNDEZ, José Luis, Léxico del marginalismo del siglo de oro, Salamanca, Universidad de Salamanca, 1976.

BAILEY, Nathan, The Universal Etymological English Dictionary, vol. II, London, E. Bell, 1721.

BELLE, Marie-Alice, “Rhetorical Ethos and the Translating Self in Early Modern England”, in Andrea Rizzi (ed.), Trust and Proof: Translators in Renaissance Print Culture, Leiden, Brill, 2018, pp. 62-84.

BERLINA, Alexandra, Brodsky Translating Brodsky: Poetry in Self-Translation, New York, Bloomsbury, 2014.

BJORNSON, Richard, “The Picaresque Novel in France, England, and Germany”, Comparative Literature, 29:2 (1977), 124-147.

BORGES, Jorge Luis, “Las versiones homéricas”, in: Obras Completas, 4 vols. Buenos Aires, Emecé Editores, 1973, pp. 239-243.

"Buscón”, Autoridades: Real Academia Española: Diccionario de la Lengua Castellana, Madrid, Francisco del Hierro, 1726-1739.

CLAMURRO, William H., “The Destabilized Sign: Word and Form in Quevedo's Buscón”, MLN, 95:2 (1980), 295-311.

COTTEGNIES, Line, “'That Famous Wit and Cavaleer of France': The English Translation of Cyrano de Bergerac in the 1650s”, Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée, 46:2 (2019), 318-335.

DICKIE, Simon, Cruelty and Laughter: Forgotten Comic Literature and the Unsentimental Eighteenth Century, Chicago-London, The University of Chicago Press, 2011.

ETTINGHAUSEN, Henry, “Quevedo's Converso Pícaro”, MLN, 102:2 (1987), 241-254.FERNÁNDEZ, Enrique and Joseph T. SNOW, A Companion to Celestina, Leiden, Brill, 2017.

FRIEDMAN, Edward H., “The Baroque Picaro Francisco de Quevedo’s Buscón”, in Juan Antonio Garrido Ardila (ed.), The Picaresque Novel in Western Literature From the Sixteenth Century to the Neopicaresque, Cambridge UP, 2015, pp. 75-95.

FRYE, David, “Introduction”, Lazarillo de Tormes and The Grifter (El Buscon): Two Novels of the Low Life in Golden Age Spain, translated by David Frye, Indianapolis, Hackett Publishing Company, 2015, pp. viii-xxxv.

FUCHS, Barbara (ed.), Knowing Fictions: Picaresque Reading in the Early Modern Hispanic World, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021.

GARRETT, Matthew, “Subterranean Gratification: Reading after the Picaro”, Critical Inquiry, 42:1 (2015), pp. 97-123, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/ 682997. Accessed 20 July 2024.

GARZELLI, Beatrice, Traducir El Siglo De Oro: Quevedo y sus contemporáneos, New York, IDEA/IGAS, 2018.

GHERARDI, Flavia, and Manuel Angel CANDELAS COLODRÓN (eds.), La transmisión de Quevedo, Vigo, Editorial del Hispanismo, 2015.

GIBSON, William, “Tobias Smollett and Cat-for-Hare: The Anatomy of a Picaresque Joke”, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 40:4 (2007), 571-586.

GUILLÉN, Claudio, “From Literature as System: Essays toward the Theory of Literary History”, in: Michael McKeon (ed.), Theory of the Novel: A Historical Approach, Baltimore-London, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000, 34-50.

HARMAN, William, A Caveat or Warning for Common Cursitors, Vulgarly Called Vagabonds (1566), in: Arthur F. Kinney, Rogues, Vagabonds, & Sturdy Beggars: A New Gallery of Tudor and Early Stuart Rogue Literature Exposing the Lives, Times, and Cozening Tricks of the Elizabethan Underworld, Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press, 1990.

IVENTOSCH, Herman, “Onamastic Invention in the Buscón”, Hispanic Review, 29:1 (1961), 15-32.

KATONA, Anna, “From Lazarillo To Augie March A Study Into Some Picaresque Attitudes,” Angol Filológiai Tanulmányok / Hungarian Studies in English, 4 (1969), 87-103.

KNOWLTON, John F., “The Untranslatable: Translation as a Critical Tool”, Hispania, 50:1 (1967), 125-128.

LAURENTI, Joseph L., Catálogo bibliográfico de la literatura picaresca, siglos XVI-XX, Kassel, Reichenberger, 1988.

NEBRIJA, Elio Antonio de, Vocabulario español-latino, Alicante, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, [1495?] 2005.

PÉREZ FERNÁNDEZ, José María, “The Picaresque, Translation and the History of the Novel”, in: Curso “La comunicación intercultural eurasiática en las condiciones del proceso de Bolonia”, Centro Mediterráneo (Universidad de Granada), 24-28 junio de 2013, http://hdl.handle.net/10481/28072. Accessed 20 July 2024.

QUEVEDO, Francisco de, L'Aventurier Buscon, histoire facecieuse. Translated by Sieur de la Geneste, Paris, Chez Pierre Billaine, 1635.

— Geschichte und Leben des Erzschelms, genannt Don Paul. Translated by Johann Georg Keil, Leipzig, F. A. Brockhaus, 1826.

— Historia della vita del astutissimo e sagacissimo Buscone chiamato don Paulo, translated by Giovanni Pietro Franco, Venice, Presso G. Scaglia, 1634.

— La vida del Buscón llamado don Pablos, Angel Basanta (ed.), Madrid, Castalia, 1986.

PARELLO, Vincent, “'Judío, puto y cornudo': la judeofobia en el Buscón de Quevedo”, Sociocriticism 26 (2011), 245-265, http://hdl.handle.net/10481/59713. Accessed 20 July 2024.

REY, Alfonso, “The Title of Quevedo's Buscón: Textual Problems and Literary”, The Modern Language Review 105:1 (2010), 122-130.

RODRÍGUEZ, Alfred, and John P. LEDOUX, “Sobre la imagen naipesca del comienzo del “Buscón”, RILCE. Revista de Filología Hispánica, 10:2 (1994), 119-127.

RONCERO LÓPEZ, Victoriano, De bufones y pícaros: La risa en la novela picaresca, Berkeley, Iberoamericana, 2010.

ROSE, Marilyn Gaddis, Translation and Literary Criticism: Translation as Analysis, Manchester, St. Jerome, 1997.

WATTS, Henry Edward, “Quevedo and His Works”, “Introduction”, Pablo de Segovia The Spanish Sharper, by Francisco de Quevedo, London, Unwin Brothers, 1892.

WEINSTEIN, Arnold. Fictions of the Self, 1550-1800, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2016.

NOTES

(1) The failure of class mobility may be the whole point, for many critics: “Quevedo (who prided himself on his noble, Old Christian, ancestry) is out simply to humiliate this unscrupulous upstart whose social ambitions represent a threat to the class Quevedo belonged to and wrote fo” (Ettinghausen 1987: 242).

(2) Interest in the dissemination of Quevedo's work worldwide is evidenced by such publications as Gherardi and Candelas Colodrón (eds., 2015). On the picaresque, see also Joseph L. Laurenti (1988) and Fuchs (ed., 2021). For reasons of space and redundancy we will not reference Piñeda's translation (1745), or certain translated passages. The 1683 text is highly abridged and does not figure in our survey either. John Stevens' 1707 text, unusually, was revised later that century, reprinted in different works, and revised again in the twentieth; we will refer to the 1742 edition herein. The Gibson (2007) quote is from Quevedo 1742: 136.

(3) All citations from El Buscón are from Quevedo (1986 critical edition).

(4) Translations of the novel even use hybrids: Frye calls his language “steampunk-syle” (2015: xxxii): older concepts and material culture coexist with contemporary language.

(5) Pérez Fernández' reminder that picaresque tales not only were potentially taken to be journalistic and veridical at the time of their origins, but also have intersections with spiritual biographies, is illuminating here: whereas the saint's journey, though, is “from sin to salvation, [...] pícaros and rogues evolve from poverty and deprivation towards the cynical assimilation of the self-interested strategies and the dissimulation he or she must apply for social integration [...].” See also Rey, 2010: 127.

© Grupo de Investigación T-1611, Departamento de Filología Española y Departamento de Traducción e Interpretación y de Estudios de Asia Oriental (UAB)

© Research Group T-1611, Spanish Philology Department and Department of Translation, Interpreting and East Asian Studies, UAB

© Grup de Recerca, T-1611, Departament de Filologia Espanyola i Departament de Traducció i d'Interpretació i d'Estudis de l'Àsia Oriental, UAB